information warfare 1

Friday, December 30, 2005

BALLISTIC MISSILE-CARRYING , NUCLEAR-POWERED SUBMARINE (SSBN)

The Cold War may be over, but the United States is still keeping its powder dry, spending billions of dollars annually to maintain and upgrade its nuclear forces. As of January 2006, the U.S. stockpile contains almost 10,000 nuclear warheads. And the Bush administration's preemption policy--which allows for the quick use of nuclear weapons to destroy "time-urgent targets" anywhere in the world--is now operational on long-range bombers, strategic submarines, and presumably intercontinental ballistic missiles..(link)

Typhoon Class submarine

U.S. nuclear forces, 2006

Strategic Submarine Proliferation

Project 955 Borey (SSBN)

Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD)

Modernization of Strategic Nuclear Weapons In Russia

The Russian Military

Type 941 "Typhoon" Class Specifications

Newest ballistic missile

941 Typhoon images

Ballistic missile submarine diagram 1

Ballistic missile submarine diagram 2

IMAGES (from top):

-Typhoon showing missile hatches

-Ohio SSGN

-Trident II D-5 SLBM (UGM-133A) (British)

-Ohio (SSBN)

The Cold War may be over, but the United States is still keeping its powder dry, spending billions of dollars annually to maintain and upgrade its nuclear forces. As of January 2006, the U.S. stockpile contains almost 10,000 nuclear warheads. And the Bush administration's preemption policy--which allows for the quick use of nuclear weapons to destroy "time-urgent targets" anywhere in the world--is now operational on long-range bombers, strategic submarines, and presumably intercontinental ballistic missiles..

links

IMAGES (from top):

-Typhoon showing missile hatches

-Ohio SSGN

-Trident II D-5 SLBM (UGM-133A) (British)

-Ohio (SSBN)

Wednesday, December 28, 2005

MUTUAL ASSURED DESTRUCTION

This was the infamous Cuban missile crisis of the early 1960s, an episode that is described in the book, "Games for Business and Economics" (Gardner, 1995) with the diagram above. (link)

This was the infamous Cuban missile crisis of the early 1960s, an episode that is described in the book, "Games for Business and Economics" (Gardner, 1995) with the diagram above. (link)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (link) :

* 1 Theory

* 2 Criticism

* 3 History

. 3.1 Pre-1945

. 3.2 Early Cold War

. 3.3 Late Cold War

. 3.4 Post Cold War

* 4 MAD as official policy

* 5 See also

* 6 External links

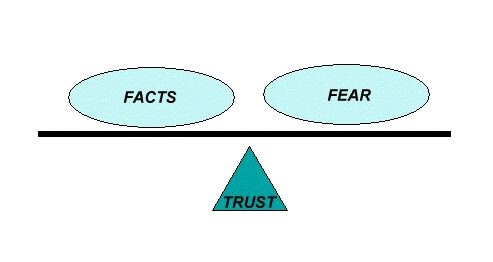

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is the doctrine of military strategy in which a full scale use of nuclear weapons by one of two opposing sides would result in the destruction of both the attacker and the defender. It is based on the theory of deterrence according to which the deployment of strong weapons is essential to threaten the enemy in order to prevent the use of the very same weapons. It is also cited by gun control opponents as the reason why crime rates sometimes tend to be lower in heavily armed populations. See also Switzerland, whose comprehensive military defense strategy has prevented potential enemies from attempting invasions, even during World War II. The strategy is effectively a form of Nash Equilibrium, in which both sides are attempting to avoid their worst possible outcome--Nuclear Annihilation.

Theory

The doctrine assumes that each side has enough weaponry to destroy the other side and that either side, if attacked for any reason by the other, would retaliate with equal or greater force. The expected result is an immediate escalation resulting in both combatants' total and assured destruction. It is now generally assumed that the nuclear fallout or nuclear winter would bring about worldwide devastation, though this was not a critical assumption to the theory of MAD.

The doctrine further assumes that neither side will dare to launch a first strike because the other side will launch on warning (also called fail-deadly) or with secondary forces (second strike) resulting in the destruction of both parties. The payoff of this doctrine is expected to be a tense but stable peace.

The primary application of this doctrine occurred during the Cold War (1950s to 1990s) in which MAD was seen as helping to prevent any direct full-scale conflicts between the two power blocs while they engaged in smaller proxy wars around the world. It was also responsible for the arms race, as both nations struggled to keep nuclear parity, or at least retain second-strike capability.

Proponents of MAD as part of U.S. and USSR strategic doctrine believed that nuclear war could best be prevented if neither side could expect to survive (as a functioning state) a full scale nuclear exchange. The credibility of the threat being critical to such assurance, each side had to invest substantial capital even if they were not intended for use. In addition, neither side could be expected or allowed to adequately defend itself against the other's nuclear missiles. This led both to the hardening and diversification of nuclear delivery systems (such as nuclear missile bunkers, ballistic missile submarines and nuclear bombers kept at fail-safe points) and to the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

This MAD scenario was often known by the euphemism "nuclear deterrence" (The term 'deterrence' was first used in this context after World War II. Prior to that time, its use was limited to juridical terminology).

Criticism

Critics of the MAD doctrine noted that the acronym MAD fits the word mad (in this context, meaning insane) because it depended on several challengable assumptions:

* Perfect detection

- No false positives in the equipment and/or procedures that must identify a launch by the other side. The implication of this is that an accident could possibly end the world (by escalation)

- No possibility of camouflaging a launch

- No alternate means of delivery other than a missile (no hiding warheads in an ice cream truck for example)

- The weaker version of MAD also depends on perfect attribution of the launch. (If you see a launch from the Sino-Russian border, whom do you retaliate against?) The stronger version of MAD does not depend on attribution. (If someone launches at you, end the world.)

* Perfect rationality

- No rogue states will develop nuclear weapons (or, if they do, they will stop behaving as rogue states and start to subject themselves to the logic of MAD)

- No rogue commanders will have the ability to corrupt the launch decision process

- All leaders with launch capability care about the survival of their subjects

- No leader with launch capability would strike first and gamble that the opponent's response system would fail

* Inability to defend

- No shelters sufficient to protect population and/or industry

- No development of anti-missile technology or deployment of remedial protective gear. In fact, the development of effective missile defense would render the MAD scenario obsolete, because destruction would no longer be assured.

History

Pre-1945

Echoes of the doctrine can be found in the first document which outlined how the atomic bomb was a practical proposition. In March 1940, the Frisch-Peierls memorandum anticipated deterrence as the principal means of combatting an enemy with uranium weapons.

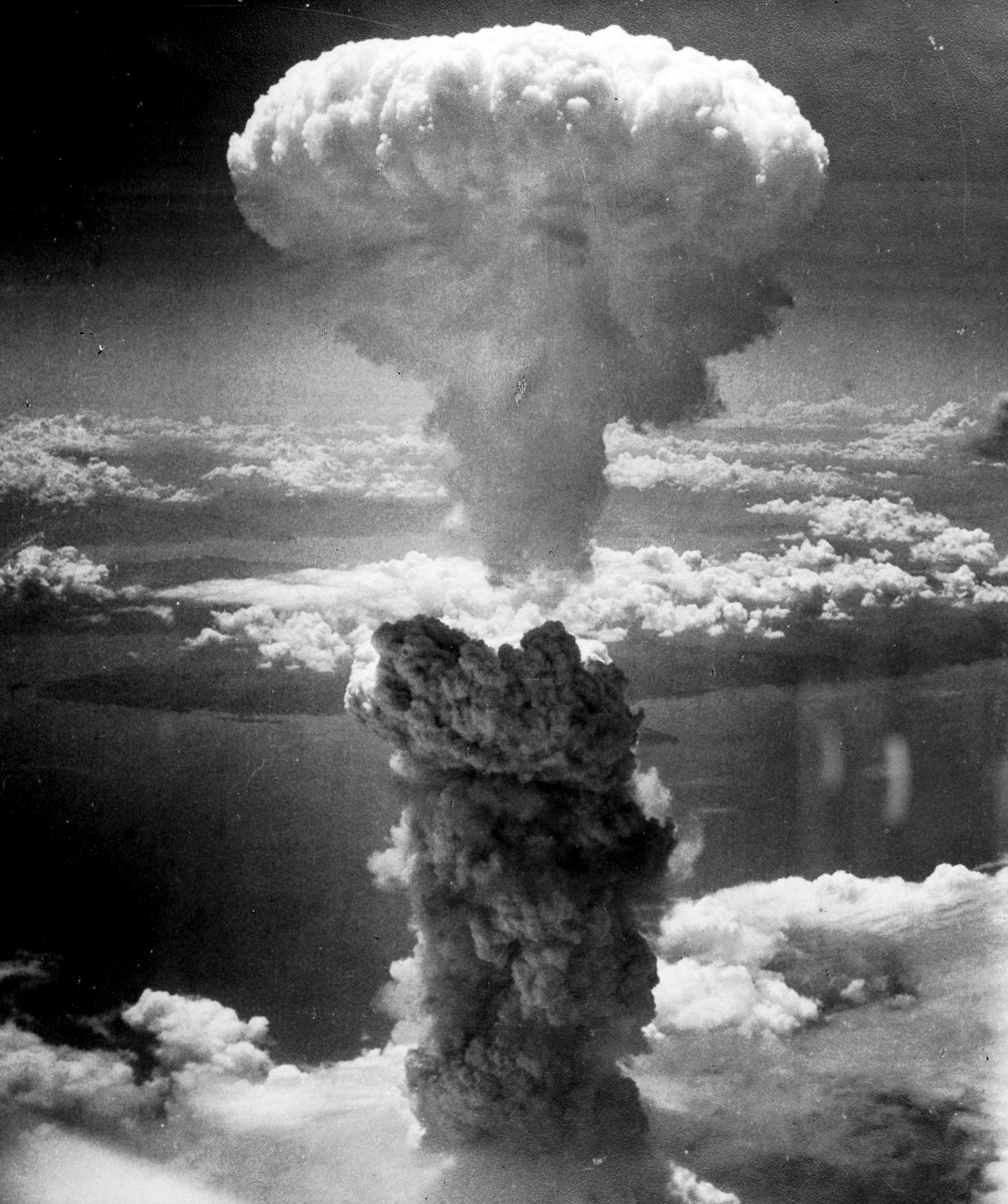

Early Cold War

In August, 1945, the United States ended World War II with the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. Four years later, on August 9, 1949, the Soviet Union developed its own nuclear weapons. At the time, both sides lacked the means to effectively use nuclear devices against each other. However, with the development of aircraft like the Convair B-36, both sides were gaining more ability to deliver nuclear weapons into the interior of the opposing country. The official nuclear policy of the United States was one of "massive retaliation", as coined by President Eisenhower, which called for massive nuclear attack against the Soviet Union if they were to invade Europe.

It was only with the advent of ballistic missile submarines, starting with the George Washington class submarine in 1959, that a survivable nuclear force became possible and second strike capability credible. This was not fully understood until the 1960s when the strategy of mutually assured destruction was first fully described, largely by United States Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

In McNamara's formulation, MAD meant that nuclear nations either had first strike or second strike capability. A nation with first strike capability would be able to destroy the entire nuclear arsenal of another nation and thus prevent any nuclear retaliation. Second strike capability indicated that a nation could promise to respond to a nuclear attack with enough force to make such a first attack highly undesirable. According to McNamara, the arms race was in part an attempt to make sure that no nation gained first strike capability.

An early form of second strike capability had already been provided by the use of continual patrols of nuclear-equipped bombers, with a fixed number of planes always in the air (and therefore untouchable by a first strike) at any given time. The use of this tactic was reduced however, by the high logistic difficulty of keeping enough planes active at all times, and the rapidly growing role of ICBMs vs. bombers (which might be shot down by air defenses before reaching their targets).

Ballistic missile submarines established a second strike capability through their stealth and by the number fielded by each Cold War adversary - it was highly unlikely that all of them could be targeted and preemptively destroyed (in contrast to, for example, a missile bunker with a fixed location that could be targeted during a first strike). Given their long range, high survivability and ability to carry many medium- and long-range nuclear missiles, submarines were a credible means for retaliation even after a massive first strike.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Soviet Union truly developed an understanding of the effectiveness of the U.S. ballistic missile submarine forces and work on Soviet ballistic missile submarines began in earnest. For the remainder of the Cold War, although official positions on MAD changed in the United States, the consequences of the second strike from ballistic missile submarines was never in doubt.

The multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV) was another weapons system designed specifically to aid with the MAD nuclear deterrence doctrine. With a MIRV payload, one ICBM could hold many separate warheads. MIRVs were first created by the United States in order to counterbalance Soviet anti-ballistic missile systems around Moscow. Since each defensive missile could only be counted on to destroy one offensive missile, making each offensive missile have, for example, three warheads (as with early MIRV systems) meant that three times as many defensive missiles were needed for each offensive missile. This made defending against missile attacks more costly and difficult. One of the largest U.S. MIRVed missiles, the LG-118A Peacekeeper, could hold up to 10 warheads, each with a yield of around 300 kilotons - all together, an explosive payload equivalent to 230 Hiroshima-type bombs. The multiple warheads made defense untenable with the technology available, leaving only the threat of retaliatory attack as a viable defensive option.

In the event of a Soviet conventional attack on Western Europe, NATO planned to use tactical nuclear weapons. The Soviet Union countered this threat by issuing a statement that any use of nuclear weapons against Soviet forces, tactical or otherwise, was grounds for a full-scale Soviet retaliatory strike. In effect, if the Soviet Union invaded Europe, the United States would stop the offensive with tactical nuclear weapons. Then, the Soviet Union would respond with a full-scale nuclear strike on the United States. The United States would respond with a full scale nuclear strike on the Soviet Union. As such, it was generally assumed that any combat in Europe would end with apocalyptic conclusions.

Late Cold War

The original doctrine of U.S. MAD was modified on July 25, 1980 with U.S. President Jimmy Carter's adoption of countervailing strategy with Presidential Directive 59. According to its architect, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, "countervailing strategy" stressed that the planned response to a Soviet attack was no longer to bomb Russian population centers and cities primarily, but first to kill the Soviet leadership, then attack military targets, in the hope of a Russian surrender before total destruction of the USSR (and the USA). This modified version of MAD was seen as a winnable nuclear war, while still maintaining the possibility of assured destruction for at least one party. This policy was further developed by the Reagan Administration with the announcement of the Strategic Defense Initiative (known derisively as "Star Wars"), the goal of which was to develop space-based technology to destroy Russian missiles before they reached the USA.

SDI was criticized by both the Soviets and many of America's allies (including Margaret Thatcher) because, were it ever operational and effective, it would have undermined the "assured destruction" required for MAD. If America had a guarantee against Soviet nuclear attacks, its critics argued, it would have first strike capability which would have been a politically and militarily destabilizing position. Critics further argued that it could trigger a new arms race, this time to develop countermeasures for SDI. Despite its promise of nuclear safety, SDI was described by many of its critics (including Soviet nuclear physicist and later peace activist Andrei Sakharov) as being even more dangerous than MAD because of these political implications.

Post Cold War

The fall of the Soviet Union has reduced tensions between Russia and the United States and between the United States and China. Although the administration of George W. Bush withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in June 2002, they claim that the limited national missile defense system which they propose to build is designed only to prevent nuclear blackmail by a state with limited nuclear capability and is not planned to alter the nuclear posture between Russia and the United States. Russia and the United States still tacitly hold to the principles of MAD.

MAD as official policy

Whether or not MAD was ever the accepted doctrine of the United States military during the Cold War is largely a matter of interpretation. The term MAD was not coined by the military but was, however, based on the policy of "Assured Destruction" advocated by U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara during the 1960s. The U.S. Air Force, for example, has retrospectively contended that it never advocated MAD and that this form of deterrence was seen as one of a number of options in U.S. nuclear policy. Former officers have emphasized that they never felt as limited by the logic of MAD (and were prepared to use nuclear weapons in smaller scale situations than "Assured Destruction" allowed), and didn't deliberately target civilian cities (though they acknowledge that the result of a "purely military" attack would certainly devastate the cities as well).

MAD was certainly implied in a number of U.S. policies, though, and certainly used in the political rhetoric of leaders in both the USA and the USSR during many periods of the Cold War. The differences between MAD and a general theory of deterrence, the latter of which was certainly embodied in both rhetoric and technological decisions made by the U.S. and USSR, varies more along the lines of strictness of interpretation than they do categorical definitions.

See also

* Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

* Doomsday clock

* Doomsday device

* NUTS (Nuclear Utilization Target Selection)

* Cold War* Strategic Defense Initiative

* Launch on warning* moral equivalence

* Essence of Decision, a book which disputes the MAD doctrine

* game theory

- Herman Kahn

* nuclear disarmament

* nuclear strategy

* Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP)

* RAND Corporation

* weapon of mass destruction

* Balance of terror

* Suicide weapon

* Nuclear missile defense

* Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, a famous 1964 Stanley Kubrick film that satirizes the MAD situation.

* Red Alert, the Peter George book upon which Dr. Strangelove is based.

* Fail-Safe, a second film that takes a more-serious view of the MAD situation.

* WarGames, presented MAD by juxtaposing human fear with computed game theory

* Stanislav Petrov, Soviet colonel who may have averted World War III

* Force de frappe

Weapons of mass destruction Cuban Missile Crisis Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov, a nuclear war averting incident during the Cuban Missile Crisis Nuclear weapons Nuclear warfare Military doctrines

External links

* In the Shadow of MAD, an article critical of the idea of MAD as US policy.

* Herman Kahn's Doomsday Machine

* Excerpts of Gorbachev-Reagan Reykjavik Talks, 1986 (regards SDI as a threat to MAD)

* Robert McNamara's "Mutural Deterrence" speech from 1962

* Nuclear Files.org Mutual Assured Destruction

20 Mishaps That Might Have Started Accidental Nuclear War

Categories: Cold War | Nuclear strategies | Nuclear weapons | Nuclear warfare | English phrases | Military doctrines | Political neologisms

This was the infamous Cuban missile crisis of the early 1960s, an episode that is described in the book, "Games for Business and Economics" (Gardner, 1995) with the diagram above. (link)

This was the infamous Cuban missile crisis of the early 1960s, an episode that is described in the book, "Games for Business and Economics" (Gardner, 1995) with the diagram above. (link)From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (link) :

* 1 Theory

* 2 Criticism

* 3 History

. 3.1 Pre-1945

. 3.2 Early Cold War

. 3.3 Late Cold War

. 3.4 Post Cold War

* 4 MAD as official policy

* 5 See also

* 6 External links

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is the doctrine of military strategy in which a full scale use of nuclear weapons by one of two opposing sides would result in the destruction of both the attacker and the defender. It is based on the theory of deterrence according to which the deployment of strong weapons is essential to threaten the enemy in order to prevent the use of the very same weapons. It is also cited by gun control opponents as the reason why crime rates sometimes tend to be lower in heavily armed populations. See also Switzerland, whose comprehensive military defense strategy has prevented potential enemies from attempting invasions, even during World War II. The strategy is effectively a form of Nash Equilibrium, in which both sides are attempting to avoid their worst possible outcome--Nuclear Annihilation.

Theory

The doctrine assumes that each side has enough weaponry to destroy the other side and that either side, if attacked for any reason by the other, would retaliate with equal or greater force. The expected result is an immediate escalation resulting in both combatants' total and assured destruction. It is now generally assumed that the nuclear fallout or nuclear winter would bring about worldwide devastation, though this was not a critical assumption to the theory of MAD.

The doctrine further assumes that neither side will dare to launch a first strike because the other side will launch on warning (also called fail-deadly) or with secondary forces (second strike) resulting in the destruction of both parties. The payoff of this doctrine is expected to be a tense but stable peace.

The primary application of this doctrine occurred during the Cold War (1950s to 1990s) in which MAD was seen as helping to prevent any direct full-scale conflicts between the two power blocs while they engaged in smaller proxy wars around the world. It was also responsible for the arms race, as both nations struggled to keep nuclear parity, or at least retain second-strike capability.

Proponents of MAD as part of U.S. and USSR strategic doctrine believed that nuclear war could best be prevented if neither side could expect to survive (as a functioning state) a full scale nuclear exchange. The credibility of the threat being critical to such assurance, each side had to invest substantial capital even if they were not intended for use. In addition, neither side could be expected or allowed to adequately defend itself against the other's nuclear missiles. This led both to the hardening and diversification of nuclear delivery systems (such as nuclear missile bunkers, ballistic missile submarines and nuclear bombers kept at fail-safe points) and to the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

This MAD scenario was often known by the euphemism "nuclear deterrence" (The term 'deterrence' was first used in this context after World War II. Prior to that time, its use was limited to juridical terminology).

Criticism

Critics of the MAD doctrine noted that the acronym MAD fits the word mad (in this context, meaning insane) because it depended on several challengable assumptions:

* Perfect detection

- No false positives in the equipment and/or procedures that must identify a launch by the other side. The implication of this is that an accident could possibly end the world (by escalation)

- No possibility of camouflaging a launch

- No alternate means of delivery other than a missile (no hiding warheads in an ice cream truck for example)

- The weaker version of MAD also depends on perfect attribution of the launch. (If you see a launch from the Sino-Russian border, whom do you retaliate against?) The stronger version of MAD does not depend on attribution. (If someone launches at you, end the world.)

* Perfect rationality

- No rogue states will develop nuclear weapons (or, if they do, they will stop behaving as rogue states and start to subject themselves to the logic of MAD)

- No rogue commanders will have the ability to corrupt the launch decision process

- All leaders with launch capability care about the survival of their subjects

- No leader with launch capability would strike first and gamble that the opponent's response system would fail

* Inability to defend

- No shelters sufficient to protect population and/or industry

- No development of anti-missile technology or deployment of remedial protective gear. In fact, the development of effective missile defense would render the MAD scenario obsolete, because destruction would no longer be assured.

History

Pre-1945

Echoes of the doctrine can be found in the first document which outlined how the atomic bomb was a practical proposition. In March 1940, the Frisch-Peierls memorandum anticipated deterrence as the principal means of combatting an enemy with uranium weapons.

Early Cold War

In August, 1945, the United States ended World War II with the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. Four years later, on August 9, 1949, the Soviet Union developed its own nuclear weapons. At the time, both sides lacked the means to effectively use nuclear devices against each other. However, with the development of aircraft like the Convair B-36, both sides were gaining more ability to deliver nuclear weapons into the interior of the opposing country. The official nuclear policy of the United States was one of "massive retaliation", as coined by President Eisenhower, which called for massive nuclear attack against the Soviet Union if they were to invade Europe.

It was only with the advent of ballistic missile submarines, starting with the George Washington class submarine in 1959, that a survivable nuclear force became possible and second strike capability credible. This was not fully understood until the 1960s when the strategy of mutually assured destruction was first fully described, largely by United States Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

In McNamara's formulation, MAD meant that nuclear nations either had first strike or second strike capability. A nation with first strike capability would be able to destroy the entire nuclear arsenal of another nation and thus prevent any nuclear retaliation. Second strike capability indicated that a nation could promise to respond to a nuclear attack with enough force to make such a first attack highly undesirable. According to McNamara, the arms race was in part an attempt to make sure that no nation gained first strike capability.

An early form of second strike capability had already been provided by the use of continual patrols of nuclear-equipped bombers, with a fixed number of planes always in the air (and therefore untouchable by a first strike) at any given time. The use of this tactic was reduced however, by the high logistic difficulty of keeping enough planes active at all times, and the rapidly growing role of ICBMs vs. bombers (which might be shot down by air defenses before reaching their targets).

Ballistic missile submarines established a second strike capability through their stealth and by the number fielded by each Cold War adversary - it was highly unlikely that all of them could be targeted and preemptively destroyed (in contrast to, for example, a missile bunker with a fixed location that could be targeted during a first strike). Given their long range, high survivability and ability to carry many medium- and long-range nuclear missiles, submarines were a credible means for retaliation even after a massive first strike.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Soviet Union truly developed an understanding of the effectiveness of the U.S. ballistic missile submarine forces and work on Soviet ballistic missile submarines began in earnest. For the remainder of the Cold War, although official positions on MAD changed in the United States, the consequences of the second strike from ballistic missile submarines was never in doubt.

The multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV) was another weapons system designed specifically to aid with the MAD nuclear deterrence doctrine. With a MIRV payload, one ICBM could hold many separate warheads. MIRVs were first created by the United States in order to counterbalance Soviet anti-ballistic missile systems around Moscow. Since each defensive missile could only be counted on to destroy one offensive missile, making each offensive missile have, for example, three warheads (as with early MIRV systems) meant that three times as many defensive missiles were needed for each offensive missile. This made defending against missile attacks more costly and difficult. One of the largest U.S. MIRVed missiles, the LG-118A Peacekeeper, could hold up to 10 warheads, each with a yield of around 300 kilotons - all together, an explosive payload equivalent to 230 Hiroshima-type bombs. The multiple warheads made defense untenable with the technology available, leaving only the threat of retaliatory attack as a viable defensive option.

In the event of a Soviet conventional attack on Western Europe, NATO planned to use tactical nuclear weapons. The Soviet Union countered this threat by issuing a statement that any use of nuclear weapons against Soviet forces, tactical or otherwise, was grounds for a full-scale Soviet retaliatory strike. In effect, if the Soviet Union invaded Europe, the United States would stop the offensive with tactical nuclear weapons. Then, the Soviet Union would respond with a full-scale nuclear strike on the United States. The United States would respond with a full scale nuclear strike on the Soviet Union. As such, it was generally assumed that any combat in Europe would end with apocalyptic conclusions.

Late Cold War

The original doctrine of U.S. MAD was modified on July 25, 1980 with U.S. President Jimmy Carter's adoption of countervailing strategy with Presidential Directive 59. According to its architect, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, "countervailing strategy" stressed that the planned response to a Soviet attack was no longer to bomb Russian population centers and cities primarily, but first to kill the Soviet leadership, then attack military targets, in the hope of a Russian surrender before total destruction of the USSR (and the USA). This modified version of MAD was seen as a winnable nuclear war, while still maintaining the possibility of assured destruction for at least one party. This policy was further developed by the Reagan Administration with the announcement of the Strategic Defense Initiative (known derisively as "Star Wars"), the goal of which was to develop space-based technology to destroy Russian missiles before they reached the USA.

SDI was criticized by both the Soviets and many of America's allies (including Margaret Thatcher) because, were it ever operational and effective, it would have undermined the "assured destruction" required for MAD. If America had a guarantee against Soviet nuclear attacks, its critics argued, it would have first strike capability which would have been a politically and militarily destabilizing position. Critics further argued that it could trigger a new arms race, this time to develop countermeasures for SDI. Despite its promise of nuclear safety, SDI was described by many of its critics (including Soviet nuclear physicist and later peace activist Andrei Sakharov) as being even more dangerous than MAD because of these political implications.

Post Cold War

The fall of the Soviet Union has reduced tensions between Russia and the United States and between the United States and China. Although the administration of George W. Bush withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in June 2002, they claim that the limited national missile defense system which they propose to build is designed only to prevent nuclear blackmail by a state with limited nuclear capability and is not planned to alter the nuclear posture between Russia and the United States. Russia and the United States still tacitly hold to the principles of MAD.

MAD as official policy

Whether or not MAD was ever the accepted doctrine of the United States military during the Cold War is largely a matter of interpretation. The term MAD was not coined by the military but was, however, based on the policy of "Assured Destruction" advocated by U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara during the 1960s. The U.S. Air Force, for example, has retrospectively contended that it never advocated MAD and that this form of deterrence was seen as one of a number of options in U.S. nuclear policy. Former officers have emphasized that they never felt as limited by the logic of MAD (and were prepared to use nuclear weapons in smaller scale situations than "Assured Destruction" allowed), and didn't deliberately target civilian cities (though they acknowledge that the result of a "purely military" attack would certainly devastate the cities as well).

MAD was certainly implied in a number of U.S. policies, though, and certainly used in the political rhetoric of leaders in both the USA and the USSR during many periods of the Cold War. The differences between MAD and a general theory of deterrence, the latter of which was certainly embodied in both rhetoric and technological decisions made by the U.S. and USSR, varies more along the lines of strictness of interpretation than they do categorical definitions.

See also

* Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

* Doomsday clock

* Doomsday device

* NUTS (Nuclear Utilization Target Selection)

* Cold War* Strategic Defense Initiative

* Launch on warning* moral equivalence

* Essence of Decision, a book which disputes the MAD doctrine

* game theory

- Herman Kahn

* nuclear disarmament

* nuclear strategy

* Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP)

* RAND Corporation

* weapon of mass destruction

* Balance of terror

* Suicide weapon

* Nuclear missile defense

* Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, a famous 1964 Stanley Kubrick film that satirizes the MAD situation.

* Red Alert, the Peter George book upon which Dr. Strangelove is based.

* Fail-Safe, a second film that takes a more-serious view of the MAD situation.

* WarGames, presented MAD by juxtaposing human fear with computed game theory

* Stanislav Petrov, Soviet colonel who may have averted World War III

* Force de frappe

External links

* In the Shadow of MAD, an article critical of the idea of MAD as US policy.

* Herman Kahn's Doomsday Machine

* Excerpts of Gorbachev-Reagan Reykjavik Talks, 1986 (regards SDI as a threat to MAD)

* Robert McNamara's "Mutural Deterrence" speech from 1962

* Nuclear Files.org Mutual Assured Destruction

Categories: Cold War | Nuclear strategies | Nuclear weapons | Nuclear warfare | English phrases | Military doctrines | Political neologisms

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

ART, MONEY AND POWER: MORAL FRAUD, MORAL HYPOCRISY AND STUPIDITY

The most radical gesture of Piero Manzoni - the ninety cans of Artist's shit sold at the then-current price of gold - shows the power of the creative act to regenerate into art also bodily secretions.

The most radical gesture of Piero Manzoni - the ninety cans of Artist's shit sold at the then-current price of gold - shows the power of the creative act to regenerate into art also bodily secretions.

An ironic reference to the willingness of the art market to buy everything on condition that it is signed.(link)

1. Art, Money and Power (link)

By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN

PUBLISHED: MAY 11, 2005

We had "Sensation" at the Brooklyn Museum, a gift to Charles Saatchi, whose collection it advertised, and shows at the Whitney of artists (Robert Rauschenberg and Agnes Martin come to mind) virtually packaged by the gallery that represents them. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston has been renting its Monets to a casino in Las Vegas, while the Guggenheim, which gave us the atrocious "Armani," an even more egregious paid advertisement, is spending resources shopping itself around the globe while canceling shows here at home.

Every year, in one way or another, museums test the public's faith in their integrity. When P.S. 1 unveiled "Greater New York" some weeks back, the exhibition turned out to be a shallow affair in thrall to the booming art market. No one really should have expected otherwise from an event timed to coincide with the city's big contemporary-art fair. Meanwhile, P.S. 1's institutional parent, the Museum of Modern Art, the spanking new headquarters of Modernism Inc., inaugurated its exhibition program with an appalling paean to a corporate sponsor's blue-chip collection. This gave the financial services company, UBS, an excuse to plaster the city with advertisements that made MoMA seem like its tool and minor subsidiary. You can only imagine how that went over with another of the Modern's sponsors, J. P. Morgan, UBS's rival.

Now comes the Met with its current Chanel-sponsored Chanel show, a fawning trifle that resembles a fancy showroom. Sparsely outfitted with white cube display boxes and a bare minimum of meaningful text, this absurdly uncritical exhibition puts Coco's designs alongside work by the current monarch of the House of Chanel, Karl Lagerfeld.

A few years ago, a Chanel show was put off by the Met's director, Philippe de Montebello, because Mr. Lagerfeld wanted to interfere. It makes no difference whether he had a direct hand in it this time or, as the museum keeps insisting, was kept at arm's length from the curatorial process: the impression is the same, and impressions count when it comes to the reputation of a museum.

Museums deal in two kinds of currency, after all: the quality of their collections and public trust. Squander one, and the other suffers. People visit MoMA or the Met to see great art; they will even consider art that they don't know or don't like as great because the museum says so. But this delicate cultural ecosystem depends on the public's perception that museums make independent judgments - that they're not just shilling for trustees or politicians or sponsors.

Naturally, the public wonders whose pockets are greased by what a museum shows, because there's so much money involved in art. But this question can be subordinated if the museum proves that it's acting in the public's interest, and not someone else's. In turn, museums can call on the public. The New York Public Library is auctioning some American art, including a couple of Gilbert Stuarts and an Asher B. Durand that has been a civic landmark for many decades. Some New York museum ought to end up with the picture but will have to rally public enthusiasm swiftly - it will have to bank on public trust.

Of course, this is the real world. Museums need trustees to cover the bills. They depend on galleries and collectors and sponsors and artists for help. Last year, the Modigliani retrospective at the Jewish Museum had a ridiculous painting that turned out to belong to a trustee who insisted it be included. No exhibition of a living artist avoids some negotiation (read: compromise) with the artist or the artist's dealer. The artist or the dealer may demand that this picture, not that one, be shown; that new work be stressed; that a certain collector's holdings be favored; or that the show's catalog be written in a certain way. It's the cost of doing business.

But there are degrees of compromise. Some years back, the National Gallery in Washington presented a show of the collection put together by a Swiss industrialist, Emil Bührle, with a catalog overseen by his heirs that celebrated his "inner flame" for art but made no mention of the fact that his fortune came partly from dealing arms to the Nazis, or that his son, who owned many of the works, was convicted of illegal arms sales. Only the most scrupulous reader of the fine print would have noticed that a Renoir once belonged to Hermann Göring.

The show was about Bührle, so the public could expect to learn who he was. The Chanel show avoids mentioning her activities during the war, when she maintained a life in Paris as the lover of an SS officer and, according to her biographer, Janet Wallach, tried to exploit Nazi laws to wrest control of her perfume business from her Jewish partners. No doubt, the Bührle show would never have happened if the National Gallery had emphasized how Bührle sold arms to the Nazis, and I suspect Chanel would not have been very happy about sponsoring this show if the Met had been more forthcoming about its founder's wartime history.

Is such information irrelevant to what's on view? It depends.

The public should decide. The Caravaggio exhibition at the National Gallery in London makes clear that he was a murderer. His violent personality explains something about his later work. It would have been irresponsible for the exhibition not to mention it.

Trust us, museums say: the rules need to bend, and we know how much bending is enough and how much is too much. In a curious way, commercial galleries are in a better position. We see where they're coming from. Frank Lloyd Wright had a saying. At an early age he made a choice between "honest arrogance and hypocritical humility." He picked arrogance. Galleries are honest about wanting to sell you something. Museums often traffic in moral hypocrisy - and are then exploited for their presumptive lofty independence. Chanel couldn't have bought better publicity.

As for the Met, it says something that it would allow itself to play this role, just as it says something about the Modern that its first big exhibition seemed like a corporate payoff.

At least MoMA gets something. The museum will get art from UBS. Mr. Saatchi made millions recently selling Damien Hirst's shark, whose value was enhanced by the notoriety of "Sensation." All Brooklyn got was grief.

2. The Morality of Idiocy (link)

By James ford

Idiot, idiotic and idiocy are common and widely used terms, but is all idiocy the same? It can be defined as ‘Extreme folly or stupidity. A foolish or stupid utterance or deed’, and in psychological terms, ‘the state or condition of being an idiot; profound mental retardation.’ (http://dictionary.reference.com/search?q=idiocy). Other descriptive terms include absurdity, foolishness, insanity, silliness, or something that just does not have or make sense. And an idiot is a purveyor of these things/states.

My current area of research concerns the morality of idiocy. It is an area of contemporary art and culture that I am intrigued by and is also present in my artistic critical theory and studio practice. Idiocy can be a cipher for the “real” or truth. Perniola states that ‘it cannot be excluded that the artist idiot, insofar as being an interpreter of social stupidity, is the true organic artist of present society’ (Perniola 2004, p.10), and this is the starting point for my investigation. The morality/power of idiocy: is idiocy redeemable? Can it be intelligent/clever? In my opinion it is if it purveys or exposes the truth about something, brings the person or viewer closer to reality, or raises interesting/pertinent issues. Whereas real idiocy lacks all virtue and redeeming features and can only be what it is. Real idiocy can't be mobilised. The mobilisation of idiocy is a key point in this essay and by “mobilised” I mean made useful, achieves an aim, subverts, satirises, etc. Is clever idiocy morally better than real idiocy? I am more concerned with discussing redeemable idiocy, rather than the multitude of pure stupidity that surrounds us. However, I will be comparing varied examples of idiocy (focusing on art and culture), what value they have, and investigating levels and types of idiocy. When discussing types of idiocy Perniola states:

‘The connection between art and idiocy has already been pointed out by Robert Musil in the 1930s, who distinguished between two types of stupidity. There is first of all a simple stupidity, honest and naïve, that derives from a certain weakness of reason’ (Perniola 2004, p.9-10)

But in the book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (Pirsig 1999), the character/ narrator (Phaedrus) talks about “reason” being the death of quality and creativity. So this “weakness of reason” seems to be beneficial in artistic terms. Idiocy (interchangeable with the term stupidity) can be defined as an act/person/thing without reason. Phaedrus talks a lot about reason as being the thing that stunts quality and creativity. And how the ghost of reason has caused the current problems in contemporary life: apathy, emotional distance, loneliness, fear of technology, dualistic mentality; the split between the romantic and classical, esthetic and theoretical. In his book The Critique of Cynical Reason (1988), the German writer Peter Sloterdijk also focused his writings on the loss of the emotional aspect of life. Sloterdijk believes that, due to postmodern cynicism, anyone can act like an idiot and perform unprincipled actions (and get away with it) as long as their underlying critical dialogue or social commentary is seen as redeemable.

Musil’s second type of stupidity is ‘strictly related to an unstable and unsuccessful use of intelligence… the essence of stupidity consists in a certain inadequacy with respect to the functionality of life’ (Perniola 2004, p.10). This second type of stupidity is therefore dumb, worthless and not redeemable. When considering idiotic and stupid behaviour, the first things that come to mind are clowns. They may look funny (and a bit scary sometimes) but they are here to satirise. They always have to portray themselves at a level ‘lower’ than that of the audience, to make the audience members feel more important, clever and socially more adept than the clown. In this way, the clown is seen as a joke and not to be taken seriously, and therefore he can tell the truth and satirise the audience without being attacked.

One of the most well known clowns, and example of the deceptiveness of the clown guise, is Ronald McDonald. His idiocy and comical appearance makes us think that his products must be safe for children and harmless. We were duped! In the documentary film Super Size Me (Spurlock, 2004) Morgan Spurlock goes on a diet of nothing but McDonalds’ for a month, to see what results this fast food diet will do to his body. Towards the end of the film he says his diet “may be idiotic but it proves a point”. This is very interesting and redeemable idiocy. The premise of the film is certainly ridiculous and he was warned by doctors not to do it, but his childish, stubborn idiocy to see it through the full 28 days (even though his liver was turning to pate) proved that McDonalds (and fast food in general) is extremely bad for the human body, which is contrary to what the fast food chains will tell you. The film was entertaining, insightful and poignant – virtuous folly of large proportions.

People with mental illness and disorders can often behave erratically and appear dumb, crazy and idiotic (no surprise then that many viewers considered Spurlock crazy). As we will see later, this guise of mental retardation was adopted by the characters in the film The Idiots (Von Trier, 1998) – destroying/overturning certain “traditional” values to achieve the goals of their community. This subversion of normalised values is another key issue in this essay.

Idiot Culture

How idiotic is the idiocy in contemporary art and culture? In terms of classical (theoretic) and romantic (esthetical) thinking, is the work of artists such as Cattelan, Manzoni, Friedman and Creed purely juvenile with no depth or if when deconstructed classically, is their work only stupid because it is a reflection of what’s around, and thus is a truer depiction of current reality? These artists use jokes and humour in their work and, as Freud discusses in Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, jokes reveal something important that we might not want to consider directly. He saw in these jokes the problem of what determines the truth and how truth is affected by who tells it to whom.

Piero Manzoni, for me, was the original prankster. He canned his own shit, and sold it for its weight in gold, displayed his breath in a balloon, and wrote his signature on parts of people’s bodies, claiming them as living art works (fig.01, p.6). His work and idiocy has virtue in the way he was criticising art and himself by showing that anything is art if the artist says so, and all it needs is the artist’s signature to validate it, thus stimulating debate on authorship and the purpose and value of art.

The latter day Manzoni, Maurizio Cattelan, identifies the vulnerable points of a system in order to highlight them - not in a provocative and obvious way, but though imitating them or availing of their own intrinsic methods. He specialises not in Dadaist aggression but in slight shifts of reality that are a bit pathetic, a bit embarrassing, a bit silly. For instance, in 1994 Cattelan had a party costume, in the form of a huge pink cock, tailored for a French gallery owner who had to wear it during the whole exhibition (fig.02, p.6). Errotin Le Vrai Lapin (Cattelan, 1994) was striking precisely because it was so ludicrous: aggressive anti-art gestures and extreme acts have long since been accommodated into commercial art dealing, but to have a dealer make a fool of himself goes some way beyond the call of duty. In a similar way, in another show, he made a site specific work where the gallery owners/invigilators had to ride a tandem bike to power the gallery lights because he wasn’t happy with his basement exhibition space, where there was no natural light. Another contemporary artist who subverts gallery traditions is Martin Creed. With his minimal use of blue tack, scrunched paper (fig.03, p.6) and lights going on & off, Creed’s work is seen as stupid with no redeeming features, by the majority of public gallery goers.

On the subject of being devoid of redeemable content, take for example the band Goldie Lookin Chain CD track.01. No-one really knows if they are actually idiots or very good at acting like idiots. Goldie Lookin Chain (GLC) are a group of neo 80s throw-back rappers, in the style of the Beastie Boys, but GLC are “chavs” (a Chav is a council estate bred, fake logo wearing, tax dodging lay-about). Their songs are about small town Wales, Chav culture, drugs, and general laddish behaviour. Again, products of their environment, but you are never sure if they are acting like chavs or if they actually ARE chavs, thus real idiocy, not subversive or redeemable apart from cheap laughs. In one song in particular, ‘Self Suicide’ (Goldie Lookin Chain, 2004), they seem to be purely taking the piss out of dead people and musicians that have supposedly committed suicide as a way to make more money. One line says ‘I’m not gonna fall off the roof like the flid Rod Hull’. Very black humour. I can see their point that a lot of dead musicians still manage to put out records after they’re dead (the record label’s doing) and how suicide gets you notoriety and media coverage, but at the same time, the actual person who is dead or who committed suicide isn’t benefiting financially themselves, as he is dead. So the “moral” of their song is actually an idiotic oxymoron, and not really redeemable. Do GLC have any virtue, if they behave like idiots but you are not sure if they're acting? Is that the worst kind of idiocy because you gain nothing from their music and you know that they could actually be intelligent, but choose to be idiotic? That’s like wiping your arse with your hand when there is perfectly good, soft toilet paper nearby to do the job.

The Streets CD track.02 and Eminem CD track.03 are seen as crude and juvenile, but they are products of their environment and their music reflects aspects of present day society/culture. So critics of their music should take a look around. The best art has always mirrored what’s around. The music of Mike Skinner (The Streets) relates to the everyday person on the street, but particularly the average British bloke. Skinner talks about things we can connect with and situations most of us have been in ourselves, which draws us into his lyrics and songs. He’s also a very good story teller; a contemporary poet writing quite obvious songs, but they are a critique on modern youth culture (thus telling the truth about an area of society), simple beautifully told stories that everyone can have some connection with.

The Darkness are idiotic as well, but in a more slap-stick satirical way. Their actual lyrics are great and quite dark sometimes, but because of the camp look and “stadium rock” music, the real content of the songs is masked, so they can be subversive. For example, ‘Givin’ Up’ CD track.04 (The Darkness, 2003) is an up-beat tempo, cheery, Status Quo type song, whose lyrics are actually about the dangers of heroin, what it makes you do, and how hard it is to give up. But unless you listen really hard you’ll miss the point. Stupidity can be an affective guise for subversion.

‘My mamma wants to know

Where I'm spending all my dough

Honey, all she does is nag, nag, nag

But I won't apologise

I'd inject into my eyes

If there was nowhere else to stick my skag

All I want is brown

And I'm going into town

Shooting up as soon as I'm back

My friends have got some good shit

All I want is some of it

Gimme, gimme, gimme that smack

Well I've ruined nearly all of my veins

Sticking that fucking shit into my arms’

(The Darkness, 2003)

Subversive Stupidity

When used as a tactic, idiocy is a great camouflage. The animated TV series South Park exposes the hypocrisy and idiocy of Middle America through the guise of a cartoon. Also from the makers of South Park is the puppet feature film Team America: World Police (Parker, 2004). It is seen as dumb and crass but some points in the film are very satirical and poignant. Feel free to substitute the terms George Bush, Tony Blair and Terrorists into this quote, as you see fit:

‘Well the truth is that Team America fights for the billion-dollar corporations. They are just as bad as the enemies they... fight.

Oh no we aren't! We're dicks! We're reckless, arrogant, stupid dicks! And the Film Actors' Guild! are pussies. And Kim Jong Il!.. is an asshole. Pussies don't like dicks!.. because pussies get fucked by dicks. But dicks also fuck assholes. Assholes who just want to shit on everything. Pussies may think they can deal with assholes their way, but the only thing that can fuck an asshole... is a dick... with some balls. The problem with dicks is that sometimes they fuck too much, or fuck when it isn't appropriate,... and it takes a pussy to show 'em that. But sometimes pussies get so full of shit that they become assholes themselves. Because pussies are only an inch and a half away from assholes. I don't know much in this... crazy, crazy world, but I do know that if you don't let us fuck this asshole, we are gonna have our dicks and our pussies!... all covered in shit.’

In the film Constantine (Lawrence (II), 2005), Satan is portrayed as a little bit camp, and in South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut (Parker, 1999), he is full-on queer (see fig.05, p.9). Thus the devil is portrayed as homosexual in an idiotic, juvenile way that belittles Christians’ beliefs of him as a fierce, dangerous enemy. But this comedic campness disguises the fact that they are satirising the idiotic beliefs of Christians that think that gays are evil and in league with the devil. The idiocy and ridiculousness of the notion of Satan being a complete Queen softens the truth that is actually being told; that it is stupid to think of homosexuality as evil and sinful and that the Christian faith should redress their bigoted ideals.

Idiocy by one person or group can expose the truth, idiocy and stupidity in others. By appearing as a harmless idiot, Ali G and Borat (Ali G in da USAiii, Channel 4, 2003) lure their targets into a false sense of security and thus can expose their idiocy. Sacha Baron Cohen is brilliant, in his character guises as Borat and Ali G, for showing people in their true colours. Borat Sagdiyev is ‘Kazakhstan's sixth most famous man, a top journalist for the state TV network in the USA to offer his own unique take on the American dream’

(http://www.channel4.com/entertainment/tv/microsites/A/alig/borat.html).

In episode three of the second series of Ali G in da USAiii (2003), Borat ventures to a hick country western bar and gets on stage to sing a song about the hatred of Jews in his home country of Kazakhstan (fig.06, p.12). Ironically, Baron Cohen is Jewish himself. The stupid Americans sung along with it - mob mentality - and mindlessly joined in without realising what they were singing:

‘In my country there is problem

And that problem is the Jew

They take everybody money

And they never give it back

Throw the Jew down the well

So my country can be free

You must grab him by his horns

Then we have a big party’ CD track.05

This notion of the acts/idiocy of someone else exposing the idiocy/stupidity in others leads me to talk about Brass Eye (2001): a satirical news parody series, created by Chris Morris, most famous for the controversy over the paedophile episode (fig.07, p.12).

‘Gerald Howarth, Tory MP for Aldershot, told BBC Radio 4's Today programme … "Paedophilia is a very, very serious issue. To make light of it is simply sick.”

But Matthew Baker, of Channel 4, rejected the criticism, saying: "We believe that fundamentally they are missing the point of the programme. It satirised the way the media covers the issue which we believe is encouraging a dangerous atmosphere." An angry Mr Howarth dismissed this defence as "garbage".’

(http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/tv_and_radio/1461240.stm)

This episode of Brass Eye clearly hit a nerve, but did it go too far with its idiocy? Its intention was good but was its message lost in the stupidity and crude-ness of the show? It was hilarious in its outrageous portrayal of paedophiles and the paranoia of the public and media on protecting the children. It was actually satirising the paedophile hysteria caused by tabloids, and it worked brilliantly because the tabloids then caused hysteria about that Brass Eye episode, highlighting the tabloids own idiocy! In relation to Brass Eye, the book Stupidity (Ronell 2003) explores the urgency of stupidity, its hiding places as well as its everyday public appearances. It maps areas of thought in which stupidity has been traditionally concealed or repressed and tunes into stupidity in the realms of literature, philosophy and politics:

‘Neither a moral default nor a pathology, stupidity has no duty to truth yet nonetheless bears ethical consequences. At the same time there is something about stupidity - what Musil and Deleuze locate as "transcendental stupidity"- that is untrackable; it evades our cognitive scanners and turns up as the uncanny double of mastery or intelligence.’ (http://www.press.uillinois.edu/f01/ronell.html)

Idiocy is the best disguise for subversion because idiots are presumed to be stupid and harmless. We’ve all done the old chestnut, at some point, of acting all naïve and innocent (stupidly vacant) if we’ve done something wrong and we want to mislead/deceive the person we’ve done it to. A great example is the villain in The Usual Suspects (Singer, 1995). Sorry to ruin the film but the evil villain is actually the idiot. He is the one character least suspected (by the other characters) of being a big crime lord because he’s seen as weak, harmless and has a limp, but it’s all a deceptive act.

Superman is German

The super hero’s alter ego is always wimpy and a bit simple/idiotic, so no-one will suspect that their secret identity is that of a superhero. Superman, Spiderman and He-Man are examples of heroes with idiot/simpleton, bumbling fool, dork alter egos. There is a great monologue by the character Bill in Kill Bill Volume 2 (Tarantino, 2004) about Clark Kent. The essence of Bill's speech is that - unique to Superman - Clark Kent is the alias, unlike, say, Spider-Man, who's really Peter Parker, or Batman, who's really Bruce Wayne. Kent represents Superman's view of human beings, i.e., that we're all ‘weak, unsure, cowardly.’ Comics and super heroes are seen as childish and the people in the comics/films who can’t figure out that Clark Kent is Superman, when all he does is take his glasses off and slick his hair back, are definitely stupid. The German word Übermensch was incorrectly translated to the English language as “superman” and was what inspired the creation of that comic book character in the first place.

Übermensch was a theory/state of mind written about by Friedrich Nietzsche. The Übermensch lives according to the principles of his “Will to Power” which ends in complete independence. He is already fully aware of his freedoms and knows how to use them. The literal translation is “Overman”, as in a man in control OVER his own world, someone who doesn’t follow social dogma and tradition just because it’s there. We learn from parents and teachers about how to behave and life rules to follow, but an Übermensch makes their own rules and define their own lives.

Referring to Phaedrus in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, ‘For him Quality …. can never really be accepted here [in normal everyday life] because to see it one has to be free from social authority’ (Pirsig 1999, p.392). So he is basically confirming the message of the Übermensch, in that to be able to see quality and the truth (and therefore be more “real” and closer to reality) you have to be free from socio-political slave mentality. The Idiots is Danish filmmaker Lars von Trier's 1998 exploration of normality as a social system and the constraints it places on individuals to behave in prescribed ways, even under abnormal circumstances. The film chronicles the escapades of a small group of young middle-class men and women who have formed an organization to upset what they perceive to be bourgeois principles and participants, that is, well-to-do and unscrupulous people. The group attempts to accomplish its goals by acting as if they are mentally challenged, so as to annoy the gentlefolk with their "spazzing" (spastic behaviour), and interacting with each other within the confines of their private commune. Were they spazzing out as a way to truly lose all their inhibitions and to feel more real? And to be free of social tradition/etiquette? The act of stupidity as being a way to freedom. Here they create their own subculture with behaviours very different from those enforced by conventional society, which, of course, allows for extensive comical nudity and poor table manners.

The fools in Jackass (MTV, 2003) and Dirty Sanchez (MTV, 2003) also get naked and behave badly (and hurt each other a lot). I believe that this is what the people in these shows are actually like in real life; therefore the idiocy is irredeemable real stupidity. Jackass has some planning and production values and is sometimes quite clever with its ideas, whereas Dirty Sanchez is always mindless self-harming. Is Dirty Sanchez devoid of sentiment? Worthless apart from in mindless entertainment value?

The French philosopher Clement Rosset introduced the notion of idiocy to point to the accidental and determined character of the real. The term idiocy can mean stupid and without reason, but also ‘simple, particular, unique (from ancient Greek idiôtés). The real, therefore, is idiotic precisely because it only exists for itself and is incapable of appearing in any other way than what it is.’ (Perniola 2004, p.4)

Examples of this “honest stupidity” and portrayal of the idiotic real are the reality TV show The Simple Life (FOX, 2004) starring Paris Hilton & Nicole Ritchie, and the Japanese endurance game show Takeshi’s Castle (Challenge TV, 2004). They are what they are: idiotic, mindless entertainment. Ali G, Borat, and Brass Eye have another agenda and self knowledge about what they're doing whereas Paris Hilton, Nicole Ritchie and the Japanese contestants are exposing themselves as being actual idiots. This kind of real stupidity isn’t interesting because it has no value. But it is funny and quite entertaining, which makes these programmes engaging in a strange voyeuristic way. Which is better: intellectually interesting or entertaining idiocy? Takeshi’s Castle has the entertainment value, which gives it some redemption, but it’s also interesting to think about what would drive the Japanese contestants to want to take part. Perhaps they do it for the act of public humiliation and foolishness (relating to the “spazzers” in The Idiots) that then releases them from the restraints of polite Japanese society? Probably not.

Foolish Child

Innocence, naivety and vacancy allow you to speak the truth without adverse reaction. Foolishness might be the best way to subvert and tell the truth, without overtly shouting it. The Court Jester is important in King Lear (Shakespeare 1994) because he tells the king the truth. The fool demonstrates to Lear the truths about people around him, and tries to point out what treachery and deceit they wish upon him. The fool also helps Lear by pointing out certain truths about people, as well as flaws in his very own actions.

Idiocy can be a guise for subversion or a way of telling the harsh truth without getting the backlash reaction, because people aren't really listening properly to an "idiot". For example, children and “simple” adults are seen as harmless, innocent, and sometimes idiotic and stupid. Children are honest because they haven’t yet fully learnt manners, subtlety and they haven’t any reason not to speak the truth. Also, they haven’t cottoned on to the “unwritten rules” of social etiquette, something that the Übermensch strives against. But the young can be very perceptive. In The Emperor's New Clothes (Andersen 2000) it was a child who pointed out that the Emperor was actually naked, when all his advisors said he was wearing fabulous new clothes:

’The emperor walked in the procession under his crimson canopy. And all the people of the town, who had lined the streets or were looking down from the windows, said that the emperor's new clothes were beautiful. "What a magnificent robe! And the train! How well the emperor's clothes suit him!"

None of them were willing to admit that they hadn't seen a thing; for if anyone did, then he was either stupid or unfit for the job he held. Never before had the emperor's clothes been such a success.

"But he doesn't have anything on!" cried a little child.

"Listen to the innocent one," said the proud father. And the people whispered among each other and repeated what the child had said.’

(Anderson 2000, p.28)

As we have seen, cartoons can be overtly satirical and cutting, but they can also slip messages past the most observant of us. Early cartoons/shows like Captain Pugwash (BBC, 1957), The Magic Roundabout (Channel 4, 1965) and The Moomins (BBC1, 1983) contained subliminal messages and double entendres which, at first, were over looked by adults because the shows were seen to be harmless, innocent and “for kids”. Therefore it could be very subversive without being noticed. Whereas Captain Pugwash contained juvenile double entendre and The Magic Roundabout conveyed messages about drugs, The Moomins (fig.08, p.18) had a worthwhile subtext, which I only realised after reading the books as an adult. Tales from Moomin Valley (Jansson 1973) is a series of bizarre, short fictional stories about the Moomins and friends, but actually telling the truth and pitfalls of society. Examples of the underlying messages include problems of modern day society - anxiety, depression, obsessiveness, commodity fetish (i.e. your possessions end up owning you, featured in ‘The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters’ p.38), and identity crisis (which Moomin Pappa had in ‘The Secret of the Hattifatteners’ p.120). Tove Janssen was a brilliant author and illustrator. I remember watching The Moomins on TV and reading the books when I young, but the subtext is lost on children, because as a child you perceive it in a completely different way. Which makes me think that Jansson might have included it for the pleasure and consideration of parents reading to their children?

Clowning Crisis

Apart from the crude shock works of the Chapman Brothers, when it comes to manifestation of fun juvenility as art, Tom Friedman sticks out like a clown’s big foot. Friedman makes work that appears quite whimsical and childish, but relentlessly invents intricate objects out of a range of household materials, such as Styrofoam, masking tape, pencils, toilet paper, spaghetti, toothpicks and bubble gum. If you took a big, black trash bag and stuffed it with a bunch of the same bags, how many would fit? If you sharpen a brand-new pencil with a small, single-blade sharpener, continuing carefully all the way down to nothing, what does the resulting spiral shaving look like? These are just a couple of the ways Friedman twists the mundane into the unexpected, curious, and funny (fig.09 and fig.10, p.18).

I find it difficult to work out if this work has any virtue, apart from making us see the obvious, which is similar to what the fool was doing in King Lear, but the things that Friedman shows us are inconsequential and not worth much intellectual value. In fact, some critics talk about a “crisis” in contemporary art, in relation to juvenile and idiotic art work. Michael Archer, however, thinks differently. In his article Crisis, what crisis? Archer says:

‘Could a case not be made for examining the ‘celebration of disorganisation, weak analysis and plain adolescent naughtiness,’ rather than condemning it as inferior to revolutionary politics? … If things strike one as juvenile, if they look like clowning, buffoonery or naughtiness, that, surely, is all the more reason to consider how those appearances figure as meaning. If a work looks to be thoroughly conversant with, and implicated in the operations of the dominant forces in society, that is usually the time at which it pays to be most vigilant and to be wary of dismissing it.

The art world, though, doesn’t make it easy for us. Sometimes juvenilia and buffoonery is just that. And sometimes it’s more pernicious than that.’

(Archer 2003, p.5)

I.e. he is saying that some art exudes irredeemable idiocy.

‘Another way is to talk of what is at stake in art today and to try and see a way out of the current crisis. There is no crisis. What is there is what needs to be looked at. It can’t be pushed away pending the appearance of something more wholesome and palatable. If it fails to meet expectations, there’s an even chance that it’s the expectations that are misplaced. Art writing is not worth much. It’s over and gone as soon as it is finished.’ (Archer 2003, p.6)

Try substituting the noun “it” in this quote for “this essay”. My entire essay could be dismissed by readers as pointless and not relevant to current socio-political concerns, and because the essay’s topic is idiotic, by proxy, the whole essay is idiotic, juvenile and stupid. But then maybe that makes it worth reading…

Art (in its varied forms of visual arts, literature, music, film, etc) reflects life and society that surrounds us. Idiotic art and behaviour can have hidden/masked value so, in regards to interpreting idiocy and stupidity, don’t judge a book by its cover. Read it.

Ha Ha.

I’m a funny clown.

END.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

TEXTS

Andersen, Hans Christian 2000: The Emperor's New Clothes, London, Walker Books

Archer, Michael 2003: ‘Crisis, what crisis?’, in Art Monthly, No. 264, p.1-6

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor 1996: The Idiot, Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Editions Ltd

Freud, Sigmund 2004: Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, London, Penguin Books Ltd

Godfrey, Tony 1998: Conceptual Art, London, Phaidon Press Limited

Jansson, Tove 1973: Tales from Moomin Valley, Middlesex, Puffin Books

Macrone, Michael 2002: A little Knowledge, London, Ebury Press

Perniola, Mario 2004: Art and It’s Shadow, London, Continuum

Pirsig, Robert 1999: Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, London, Vintage

Ronell, Avital 2003: Stupidity, Illinois, University of Illinois Press

Shakespeare, William 1994: King Lear, London, Penguin Books Ltd

Sloterdijk, Peter 1988: Critique of Cynical Reason, Minnesota, University of Minnesota Press

ARTWORKS

Cattelan, Maurizio 1994: Errotin Le Vrai Lapin

Cattelan, Maurizio 1999: La Nona Ora

Creed, Martin 1995: work no. 88, 'a sheet of A4 paper crumpled into a ball’

Friedman, Tom 1994: Untitled (self-portrait carved out of a single aspirin)

Friedman, Tom 1999: Untitled (soap and pubic hair)

Manzoni, Piero 1960: Artist’s Breath

Manzoni, Piero 1961: Artist’s Shit

MUSIC

Eminem 2000: ‘Kill You’ on The Marshall Mathers LP, Interscope

Goldie Lookin Chain 2004: ‘Self Suicide’ on Greatest Hits, Atlantic

The Darkness 2003: ‘Givin’ Up’ on Permission to Land, Must Destroy

The Streets 2004: ‘Could Well Be In’ on A Grand Don’t Come For Free, Vice / 679 recordings

TELEVISION SHOWS

Ali G in da USAiii (Series 2), Episode 3: ‘Borat’s Guide to Country Music’, 2003, TV, Channel 4, United Kingdom

Brass Eye, 2001, TV, Channel 4, United Kingdom

Captain Pugwash, 1957, TV, BBC, United Kingdom

Dirty Sanchez, 2003, TV, MTV, United Kingdom

Jackass, 2003, TV, MTV, United States

South Park, Episode 79: ‘The Butters Show’, 2002, TV, Comedy Central, United States

Takeshi’s Castle, 2004, TV, Challenge TV, Japan

The Magic Roundabout, 1965, TV, Channel 4, United Kingdom

The Moomins, 1983, TV, BBC1, United Kingdom

The Simple Life, 2004, TV, FOX, United States

FILMS and VIDEOS

Lawrence (II), Francis 2005: Constantine, Warner Bros.

Parker, Trey 2004: Team America: World Police, Paramount Studio

Parker, Trey 1999: South Park: Bigger Longer & Uncut, Paramount Studio

Singer, Bryan 1995: The Usual Suspects, MGM

Spurlock, Morgan 2004: Super Size Me, The Con

Tarantino, Quentin 2004: Kill Bill, Volume 2, Miramax

Von Trier, Lars 1998: The Idiots, Zentropa Entertainment

WEB PAGES

http://dictionary.reference.com/search?q=idiocy, accessed: 15/03/05

http://www.press.uillinois.edu/f01/ronell.html, accessed: 22/03/05

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/tv_and_radio/1461240.stm, accessed: 26/03/05

http://www.channel4.com/entertainment/tv/microsites/A/alig/borat.html, accessed: 02/04/05

3. The Case Against Art (link 1, link 2)

From Primitivism.com and The Anthropik Cyclopaedia

"The Case Against Art" is an article by John Zerzan criticizing art and symbolic thought as inherently oppressive.

Art is always about "something hidden." But does it help us connect with that hidden something? I think it moves us away from it.

During the first million or so years as reflective beings, humans seem to have created no art. As Jameson put it, art had no place in that "unfallen social reality" because there was no need for it. Though tools were fashioned with an astonishing economy of effort and perfection of form, the old cliche about the aesthetic impulse as one of the irreducible components of the human mind is invalid.

The oldest enduring works of art are hand-prints, produced by pressure or blown pigment - a dramatic token of direct impress on nature. Later in the Upper Paleolithic era, about 30,000 years ago, commenced the rather sudden appearance of the cave art associated with names like Altamira and Lascaux. These images of animals possess an often breathtaking vibrancy and naturalism, though concurrent sculpture, such as the widely-found "venus" statuettes of women, was quite stylized. Perhaps this indicates that domestication of people was to precede domestication of nature. Significantly, the "sympathetic magic" or hunting theory of earliest art is now waning in the light of evidence that nature was bountiful rather than threatening.

The veritable explosion of art at this time bespeaks an anxiety not felt before: in Worringer's words, "creation in order to subdue the torment of perception." Here is the appearance of the symbolic, as a moment of discontent. It was a social anxiety; people felt something precious slipping away. The rapid development of the earliest ritual or ceremony parallels the birth of art, and we are reminded of the earliest ritual re-enactments of the moment of "the beginning," the primordial paradise of the timeless present. Pictorial representation roused the belief in controlling loss, the belief in coercion itself.

And we see the earliest evidence of symbolic division, as with the half-human, half-beast stone faces at El Juyo. The world is divided into opposing forces, by which binary distinction the contrast of culture and nature begins and a productionist, hierarchical society is perhaps already prefigured.

The perceptual order itself, as a unity, starts to break down in reflection of an increasingly complex social order. A hierarchy of senses, with the visual steadily more separate from the others and seeking its completion in artificial images such as cave paintings, moves to replace the full simultaneity of sensual gratification. Levi-Strauss discovered, to his amazement, a tribal people that had been able to see Venus in daytime; but not only were our faculties once so very acute, they were also not ordered and separate. Part of training sight to appreciate the objects of culture was the accompanying repression of immediacy in an intellectual sense: reality was removed in favor of merely aesthetic experience. Art anesthetizes the sense organs and removes the natural world from their purview. This reproduces culture, which can never compensate for the disability.

Not surprisingly, the first signs of a departure from those egalitarian principles that characterized hunter-gatherer life show up now. The shamanistic origin of visual art and music has been often remarked, the point here being that the artist-shaman was the first specialist. It seems likely that the ideas of surplus and commodity appeared with the shaman, whose orchestration of symbolic activity portended further alienation and stratification.

Art, like language, is a system of symbolic exchange that introduces exchange itself. It is also a necessary device for holding together a community based on the first symptoms of unequal life. Tolstoy's statement that "art is a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feeling," elucidates art's contribution to social cohesion at the dawn of culture. Socializing ritual required art; art works originated in the service of ritual; the ritual production of art and the artistic production of ritual are the same. "Music," wrote Seu-ma-tsen, "is what unifies."

As the need for solidarity accelerated, so did the need for ceremony; art also played a role in its mnemonic function. Art, with myth closely following, served as the semblance of real memory. In the recesses of the caves, earliest indoctrination proceeded via the paintings and other symbols, intended to inscribe rules in depersonalized, collective memory. Nietzsche saw the training of memory, especially the memory of obligations, as the beginning of civilized morality. Once the symbolic process of art developed it dominated memory as well as perception, putting its stamp on all mental functions. Cultural memory meant that one person's action could be compared with that of another, including portrayed ancestors, and future behavior anticipated and controlled. Memories became externalized, akin to property but not even the property of the subject.